The Great Basin Bristlecone Pine in the White Mountains (CA) photo by Tim Peterson

Scattered atop a few of the high mountains of California, Nevada and Utah, sits an extremely special tree, the Great Basin Bristlecone Pine (Pinus longaeva). Rooted in rocky and dry soil, they grow slowly and in isolation.

Widely considered one of the longest-lived sexually reproducing, non-clonal organisms on earth, their long lifecycle has been instrumental to the scientific community.

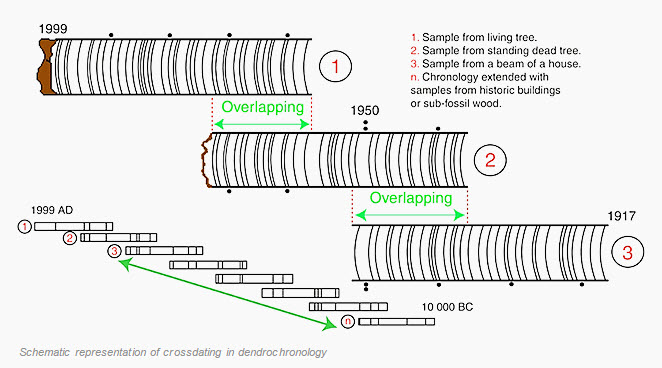

Due to the long lifespan of individual trees, and how extraordinarily slow their dead wood decays, scientists have been able to construct a continuous tree-ring chronology. This is done by comparing tree-ring samples from several different trees, both dead and alive, with the current chronology dating back over 9000 years 1.

Constructing a continuous tree-ring chronology (see Museum of Ontario Archaeology)

This process is known as dendrochronology and has been vital in helping us understand the changes in climate and atmospheric conditions through the years. These insights have also been used to recalibrate the C-14 radiocarbon dating process, helping archaeologists more precisely sketch out the timeline of the past.

Many of the discoveries and insights have only been made in the past few decades. How many more secrets do these Bristlecone Pines hold? And now consider the countless other tree species and the lessons they have yet to impart.

Getting to see these warped and distorted giants up close forced me to reflect on how much the human species has accomplished in the lifespan of just a single tree.

Take Methuselah, for instance, the namesake of the longest-living biblical character and a tree older than the bible itself. This particular tree is estimated to be around 4,850 years old and holds the record for the oldest living tree 2.

For scale, Methuselah had already begun taking root around the time the Great Pyramids of Giza were being constructed, when the human population is estimated to be less than 27 million the world over. Just pause for a moment to consider how much the planet has changed and how far we have come as a species in that time 3.

Some might argue that the incredible progress we’ve made thus far will invariably continue while others argue that nothing in the past few centuries has fundamentally changed and point to all the problems in the world as evidence.

From my perspective, we have made immense and undeniable progress in the sciences and technology, and in the strengths of our institutions which attempt to embody our values and ideals. But if the past few years have demonstrated anything, it’s that we have much work to do.

We are living in a unique moment in history, at the elbow of an exponential curve of progress and abundance, but it’s important to remember that our actions and decisions today will be felt far into the future.

We might do well to take a lesson from these ancient sentinels, a species that has traded speed for longevity.

References

1 Miller, Leonard. “Dendrochronology.” The Ancient Bristlecone Pine, www.sonic.net/bristlecone/dendro.html.

2 Brown PhD, Peter. “RMTRR OLDLIST.” Rocky Mountain Tree-Ring Research, www.rmtrr.org/oldlist.htm.

3 McEvedy, Colin and Richard Jones, 1978, “Atlas of World Population History,” Facts on File, New York, pp. 342-351.